This is going to be a long rant… and it’s about stagflation

stagflation (noun)

stag·fla·tion | \ ˌstag-ˈflā-shən\

persistent inflation combined with stagnant consumer demand and relatively high unemployment

(Merriam-Webster)

Stagflation is a mixture of slowing growth, high/steady unemployment, and high inflation. Some would say it’s absurd to mention something so harsh, citing central bank comments on the transitory nature of the recent uptick in inflation and the still notably high growth figures. But why so mad about using this term for the current state of the global economy?

It’s a delicate matter to analyze and identify the drivers of inflation to distinguish one-off factors from those that might have spillover effects, the ones that must be overlooked and the ones that must be counterbalanced with appropriate monetary policy moves – without jeopardizing growth.

Stagflation is a new phenomenon – first seen in the 70s after a supply shock in oil and in quickly killed the original Phillips curve concept (the inverse function-like relationship between inflation and unemployment) and the most puzzling part about it is that central banks have relatively limited toolset to tackle this problem.

Friedman’s monetarists prefer to control inflation first and would let the free market do the rest: allocate/direct labor force to more productive areas. Hayek’s neoclassical followers would end expansionary monetary policy and let prices adjust saying that stagflation would self-correct in time in the absence of any intervention, whereas Krugman (a modern-day Keynesian) supports government involvement to counterbalance supply side shocks as soon as possible thus hindering unemployment to rise above critical levels.

In 2020 we had a massive fall in production levels as economies came to a halt due to Covid19 (supply shock) and the processes of the recovery period were massively influenced by the monetary/fiscal responses of governments. The rebound in economic activity was sharp in 2021, demand in raw materials, energy and shipping skyrocketed and created a demand shock. Right now, central banks must choose which one to correct first, since they cannot do both at the same time.

Long story short: this is not a textbook situation, there is no “best practice” to solve this, and that frightens many.

A bit of QE history and CAPEX

Central banks became too comfortable with money printing during the last decade. They reacted to market developments instead of economic developments as if markets themselves became the economy. They poured a few hundred billions on the market as soon as volatility started to rise and gave comfort to investors who – in turn – started investing recklessly. Not surprisingly it led to mispricing of risk and misallocation of funds, in other words: this environment distorted investment policies.

And then we went “ESG”…

Let me get this straight: ESG is a good thing. Channeling funds to environmentally aware and sustainable projects is good for everyone, and it is the only path to a sustainable future. I’m not arguing with this. The problem is that investors (and advisors) carried this concept way too far.

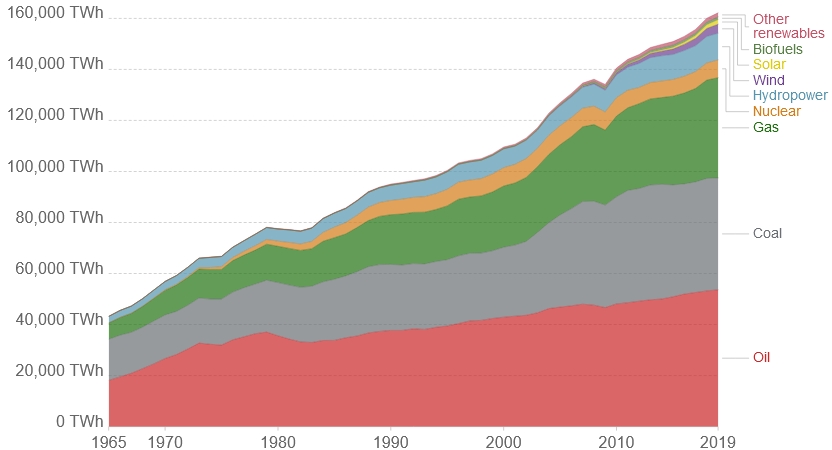

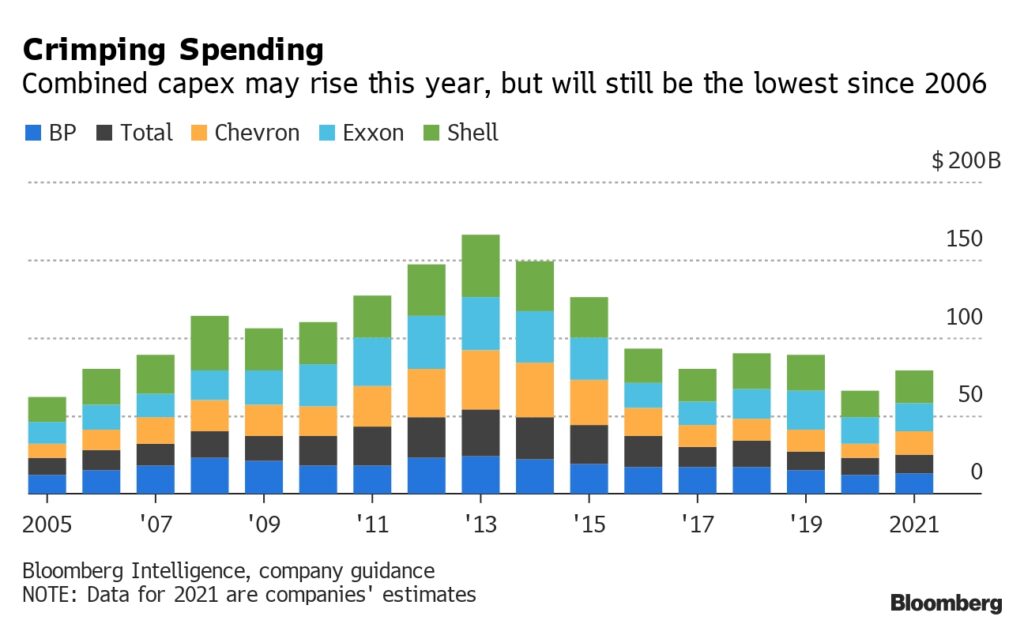

One of the casualties was the energy sector: naturally there was a setback in capital expenditure after the Great Financial Crisis (2007-2008) as global GDP and global energy consumption fell. However, capital expenditure levels failed to recover after that: most of the new money found it’s way to renewables. ESG became a buzzword, while common sense… not so much. Let me illustrate that with the following charts:

The first one shows global energy consumption and its source (the largest contributors are coal, oil and gas) the second one the capex of the big oil companies. I think you see the problem when you take a closer look at that tiny setback in consumption on the first one in 2008 and compare it to the capex flow sizes. The story of the Pikka unit in Alaska (North Slope basin) is a great example: it was one of the largest onshore finds in US history in 2013, sold to Oil Search in 2019, to a company that still struggles to find suitable investors and must postpone investment schedule.

Let’s fast forward from the post-GFC era to early 2020: economies crash landed, negative double digit GDP figures were seen everywhere, and central banks, well, poured a few hundred billions on the market. This time diminishing market utility became so obvious that stellar government spending had to be directly financed by CBs. Market recovery was fast, and industries needed energy and commodities. To the surprise of many, underfunded industries were not able to fulfill the skyrocketing new orders, bottleneck problems emerged that could neither be solved with renewables nor with other types of glittery unicorn-dreams.

The cold truth and the colder furnaces

It takes commodities to make commodities, that’s a fact that we’ve somehow forgotten. We need infrastructure spending to retool the economy to meet the energy / basic material demand, but without sufficient capex energy suppliers cannot keep up with the rising demand.

Higher energy and basic material costs are usually passed on to consumers, but with this year’s doubling or tripling heating coal and gas prices it is impossible to proceed. The result?

- Slowdown in several industrial sectors

- Capped consumer prices (energy sector)

- Producer losses

Energy producers and distributors are throwing in the towel, one after the other. After years of lacking investments, they are testing their limits (in cash) with little or no compensation and officially capped prices. I guess no one will be surprised if many more would follow.

Energy problem? Don’t stop the pipeline projects, don’t kill fossil fuel (just yet), and don’t make nuclear energy your worst enemy. Oh, and there is more: invest a huge amount into the not-so-carbon-neutral mining firms that produce metals as grid capacity is going to be the world’s next real problem.

China does it. They pump money into coal production, they support the heavy industry, and they increase their grid capacity. It’s a no brainer, just think of the EV revolution. No current electrical grid system would handle the load of everyone suddenly changing their cars to electric. Going carbon-neutral needs a lot of money, and (sorry to say) a lot of carbon. It means investments in both equipment and people to meet the needs of the EV industry. Moreover, it needs rail, ports, transmission lines, shipping.

Sounds familiar? Remember the Belt and Road Initiative?

Meanwhile, the others try to stay ESG positive or at least greenwash a few investments. I’m not sure about the success rate, to be completely honest…